In Marion's shoes - the geological story of her Alps crossing trek

“If you think adventure is dangerous, try routine, it’s lethal.” Paulo Coelho

GR5

The GR5 is a GR (“Grande Randonnée” standing for Great hiking path) that starts in the Netherlands, runs through Belgium and Luxembourg before crossing France from North to South. The alpine portion, also known as a Grande Traverse of the Alps runs from Lake Geneva (Lac Leman) to the Mediterranean sea. It is a spectacular route to hike with France showing off some of its best landscapes.

Our Product Manager and geologist, Marion Barré, has been dreaming for years to undertake this one-of-a-kind adventure. She decided to take up this challenge during August 2022, walking 620 km with 33000 m of elevation gain in 21 days. This incredible project is an opportunity for her to share with us the most remarkable alpine landscapes which diversity is explained by the regional geological history.

The French Alps are characterized by a pronounced crescent-shaped relief intersected with deep and wide valleys delineating individualized massifs with a singular geological history. These massifs are from West to East: the subalpine range, the pre-alps range, the external crystalline massifs and finally the internal zone on the edge of the Italian border.

-1200-9999.png)

In a nutshell

The Penninic thrust front is a major tectonic thrust front in the French Alps moving westward over a developing decollement horizon, (“la couche savon”) made of gypsum deposited in Triassic time, and separating the internal high grade metamorphic rocks of the Penninic nappes from the external sedimentary rocks and crystalline basement of the Helvetic nappes.

The high grade metamorphic rocks of the Penninic nappes were originally deposited as sediments on the crust that existed between the European and Apulian plates before the formation of the Alps. They are mainly characterized by ophiolite sequences and deep marine sediments, metamorphosed to phyllites, schists and amphibolites under high pressure and high temperature. The external zone crops out in Switzerland and in the French Dauphinois area. They exhibit sediments once deposited in the southern margin of the European plate. Thrusting over the decollement layer is still active today as the Apulian tectonic plate moves westward converging with the European plate.

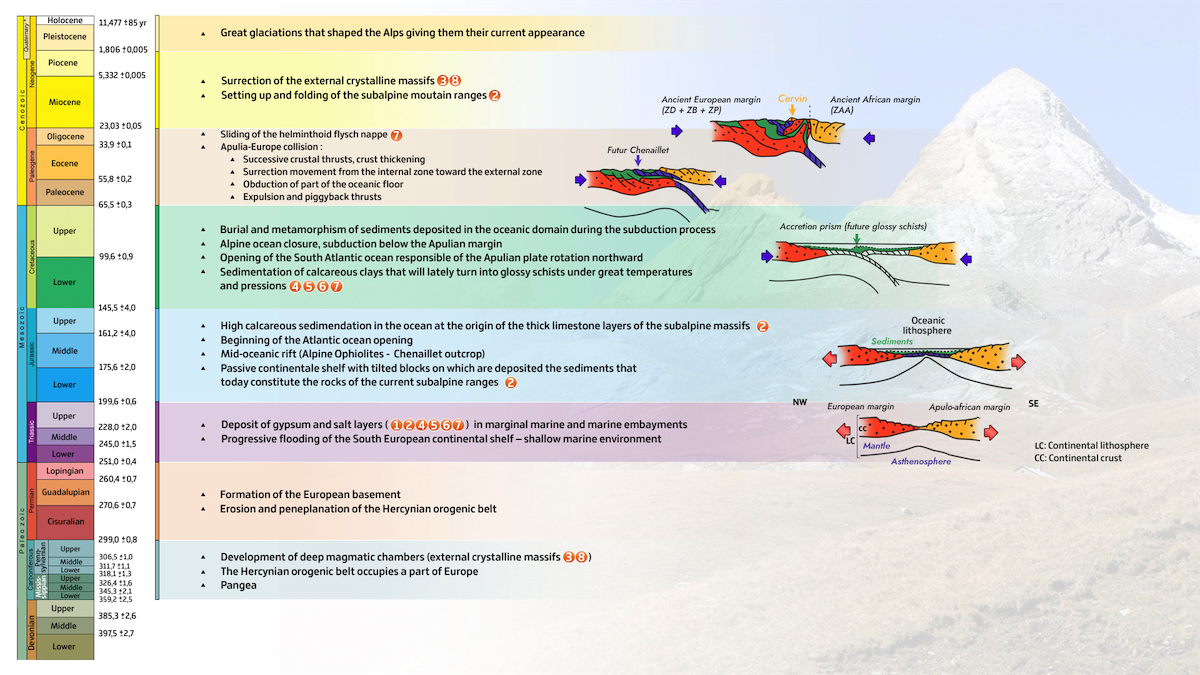

To better understand the geomorphology of the different massifs crossed along the GR5, it is important to briefly review the geological history of the French alps first.

External Zone

The Prealps massif – « Le Chablais »

The first days on the GR5 go through Le Chablais massif corresponding to the Prealps area. It shows a group of rocks from the internal domains, thrusted over the Mont-Blanc and the Aiguilles Rouges at a time when they were not yet raised. It is named klippe, where a part of the carried over materials has been isolated by erosion.

Subalpines Ranges – Haut-Giffre

The second massif encountered when going southward is called the Haut Giffre massif. It belongs to the subalpine mountainous ranges located on the outer periphery of the Alps together with 9 other massifs: Bornes, Aravis, Bauges, Chartreuse, Vercors, Dévoluy, Diois, Baronnies and Haute Provence. These massifs are mainly made of Cretaceous and Cenozoic age rocks. They are marked by very structured reliefs linked to the presence of two thick limestone levels (Tithonic limestone, of Upper Jurassic age and Urgonian limestone of Lower Cretaceous age). Marls and clay-rich limestone rocks are constitutive of the surrounding slopes.

During the Miocene, compression phases triggered the folding of the subalpine ranges located in the north. As a result, all sedimentary layers of the Helvetic zone slid westward along the detachment layer made of gypsum deposited at Triassic time.

-1200-9999.png)

External crystalline massifs – Mont-Blanc, Aiguilles-Rouges  and Argentera-Mercantour

and Argentera-Mercantour

Going southward again, we reach the breathtaking Aiguilles-Rouges and Mont-Blanc massifs belonging to the external crystalline massifs. The last massif crossed by the GR5, the Argentera-Mercantour massif, also belongs to the exernal crystalline massifs.

These high mountains are made up of crystalline rocks from the Hercynian chain, such as granites, mainly found on the high peaks, and gneiss, metamorphic rocks encountered in the peaks edges. These reliefs were developed at Miocene time and they are still rising today at a few millimeters pace a year.

- Mont-Blanc and Aiguilles-Rouges

The well-known Mont-Blanc massif is about 50 kilometers long and 15 kilometres wide along a north-east/south-west trending axis. The Mont Blanc is the highest mountain in the Alps and Western Europe, rising at 4808m above sea level. The top of the massif is made of gneiss overlying a granitic intrusion that forms the heart of the massif to the north.

To the west, the Aiguilles-Rouges massif, showing a similar orientation, consists essentially of gneiss capped by sedimentary rocks relics from the Helvetic layer carried over before the uplift of the massif. Its highest point is the Aiguille du Belvédère culminating at 2965m.

- Mercantour-Argentera

At the southern end of the Alpine arc, straddling France and Italy, lies the Argentera-Mercantour external crystalline massif. This massif consists of metamorphic rocks, micaschists, gneiss and amphibolites. These rocks are locally intersected by granitic intrusions that shape the serrated morphology of the crest with the Gélas peak being the highest point of them all rising at 3143m of altitude.

Leaving the village of St-Sauveur-sur-Tinée behind us, one can observe detritic formations (conglomerates, pelites) deposited in shallow water and resulting from the very strong erosion of the Hercynian chain during Permian time. The colour of the pebbles comes from the presence of ferric oxide and reflects a strongly oxidizing climate at that time.

Internal Zone

The internal zone of the alps starts straight to the south of the Mont Blanc. The multitude of the landscapes that can be encountered in the internal zone directly rely to the great diversity of rocks from sedimentary, metamorphic, volcanic and plutonic origins. These layers have been folded, thrusted, deeply buried then uplifted and carried over great distances during the compression period. The combination of all these processes makes geological analysis much more difficult than for external crystalline massifs.

Two main domains can be identified according to the nature of the rocks:

1. The Briançonnais domain presents a shallow sedimentary cover consisting essentially of Triassic-aged rocks, including Triassic gypsum layers, and Hercynian basement rocks (schist and sandstone) from Carboniferous to Permian age. Vanoise  , Cerces

, Cerces  / Région Ouest de Briançon

/ Région Ouest de Briançon

2. The Liguro-Piémontais domain has a thick sedimentary cover characteristic of a deep ocean bottom and consisting of a succession of schist layers made of:

- Glossy shales (Middle Upper Jurassic to Upper Cretaceous age). Vanoise

, Haute-Maurienne, Queyras

, Haute-Maurienne, Queyras

- Helminthoids Flysch (Upper Cretaceous age) which typically occurs as successive turbiditic layers deposited within deep basins rapidly formed during the subduction phase: Ubaye

Basement parts are also locally present within the internal zone:

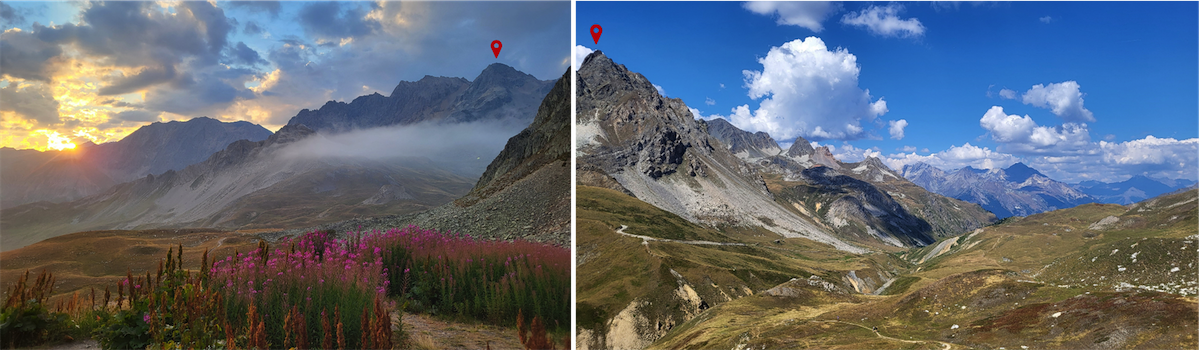

- Shreds of old ocean crust: Crete du Chenaillet/Col de Montgenèvre

- Gneiss and granite of the internal crystalline massifs: Dora Maira and Grand paradis (not crossed by the GR5)

Vanoise

The Vanoise Massif is made up of stacked thrust structures resulting from several folding events. It is well-known for its national park, the first created in France back in 1963 following the extinction of the ibex in the area. The massif culminates at the Pointe de la Grande Casse, at an altitude of 3855m.

Cerces

Leaving the Vanoise behind and crossing the valley of the Maurienne, you reach Cerces massif, also called Thabor massif, located at the Franco-Italian border. Once you have passed the Col de la Vallée Etroite, you follow the path down along a beautiful valley which is only accessible to motorists coming from Italy. The rocks in place present various types of rocks from massive limestone to dolomitic limestone deposits with layers of gypsum and cargneules locally. The Cerces massif belongs for a great part to the briançonnaise zone.

Queyras

The path to the Queyras goes through by the Col des Ayes, south of Briançon. Most of the valleys are notched in the glossy schists forming a relatively uniform relief. The tectonic structure of the Queyras is quite complex as a result of numerous folding and thrusting events.

Ubaye

The last – but not the least - massif of the internal zone that I crossed during this journey is called the Ubaye massif and is separated from the Queyras by the Col Girardin, the highest pass of the crossing (2699m). Right after this spot, the GR5 circumvents one of the most remarkable peaks of the Ubaye, the Aiguille de Chambeyron (3412m) and crosses the Haute-Ubaye which is essentially connected to the briançonnaise zone of the internal zone.

The journey ends with a nice technical downhill path along the Italian border and a well-deserved swim in the Mediterranean Sea!

Can you tell us a bit more on your experience?

Sources

Le tour de France d’un géologue, nos paysages ont une histoire. Francois Michel – BRGM edition 2008-2012

Roches et paysages, reflets de l’histoire de la Terre. Francois Michel – BRGM edition 2010

Drop us a line !

sadaqat ali 01/12/2022 17:34

Very motivational, informative and photographically rich writeup. Hats off Marion